Let's face it: this is not just about patents, laws, and keeping things even. When Steve Jobs declared "thermonuclear war" on Android, he meant it. For him it was personal, and for us it's personal. He didn't want Google's money. He wanted Google to "stop using [Apple's] ideas in Android." He felt so wronged by the alleged theft that he vowed to destroy Android. War has been declared and it is far from over.

Battles are being fought in the U.S., Europe, Asia, and Australia - virtually the entire globe. In terms of the U.S. case against Samsung, Apple claims that Samsung has committed trade dress infringement, trademark infringement, and design patent infringements and have used these as a means of unjust enrichment. Apple is basically claiming that Samsung took an iPhone, put the name Samsung on the shell and packaging box, and sold it as a Samsung device. (That's overgeneralizing to an extreme degree, but you get the point.) Before the actual trial takes place to asses whether or not Apple's claims are true, Apple asked for a preliminary injunction that would ban all sales of the Samsung products that violate the above laws (most notably, the Galaxy S and all of its U.S. counterparts and the Galaxy Tab). Apple was denied this injunction.

What we all want to know, and have been arguing about for the past nine months, is Does Apple have a case? It's clear that this is a personal issue for the company, but even so, is Samsung violating trade dress laws and infringing on Apple's patents? Now, I'm not a patent attorney so I'm not going to pretend to know the answers to those questions. However, I got in contact with a patent attorney and asked him a few questions about the case. He provided some very interesting and insightful answers, some of which surprised me.

[Greg Carr is Managing Partner of Carr LLP, a firm specializing in Intellectual Property Law. He has over 25 years of experience and has authored articles for Texas Lawyer and The National Law Journal. He is also adjunct professor of law and economics at Southern Methodist University and currently serves on the Board of Advisors for its Mechanical Engineering Department. His firm has represented General Electric Company, IBM, Nortel Networks, and many more.]

Sydney: How would you have presented your case to the courts in order to prove that Apple deserved compensation and to have Samsung's products banned?

Greg Carr: "The court did not make any determination of whether Apple's trade dress was likely infringed. Apple did not rely on its trade dress to seek a preliminary injunction. Instead, Apple based its request for a preliminary injunction (prior to trial) on its 'design' and 'utility' patents.

"Had Apple proved to the court at this stage in the case that its trade dress was likely infringed, there would have been a greater chance of Apple getting a preliminary injunction against Samsung."

True to the point, the court documents outlining the judges decision to not grant an injunction clearly state, "It is the design patents that are at the core of this preliminary injunction motion."

Essentially, trade dress is anything that contributes to the overall look and feel of a product and that is used by customers to identify the source of a product. This can include colors, fonts, packaging, a logo, symbols, and much more. Relating to this case, it could be the symbol of an apple or, according to Apple, four rows of sixteen square icons whose shape and style are allegedly being copied, to name one example.

Mr. Carr commented on why trade dress infringement is so damaging and related it to the case of Apple vs. Samsung.

GC: "Trade dress infringement causes the distinctiveness and value of Apple's trade dress to drop, as well as causing a loss of control by Apple of its own reputation. If a significant portion of the public thinks Samsung products are Apple products, then any problems with Samsung products would damage the reputation of Apple. Conversely, the favorable reputation associated with Apple's products would unfairly benefit Samsung products purchased by confused customers." (Emphasis added)

So, you can see why this is a big case. We look at is as Apple simply being upset that Samsung "stole" its design, but the problem comes when (or if) customers confuse the products and associate Samsung's failings as a failing of Apple. According to U.S. Code 15 U.S.C. § 1125, the Burden of Proof will fall on Apple. Apple will have to prove there is a likelihood that consumers will be confused. However, regarding the patent infringements, the burden of proof falls on Samsung to produce "evidence of invalidity", essentially saying that a patent is invalid for whatever reason(s) Samsung presents and should not have been granted.

As Mr. Carr and the Court brought out, this preliminary injunction dealt primarily with the patent infringement claims and did not touch on trade dress infringement. This is an area where Apple arguably has a much stronger case, though it is still not a sure win. Because we are discussing the Motion for Preliminary Injunction and this did not focus on trade dress, we will focus on patent infringement. Trade dress is an entirely different subject that may be discussed in future reports should it come up again.

Now, this is just an analysis of the assertions themselves. What we want to know is, Does Apple have a case?

Here's an argument that I've heard a lot and it's one that I've used myself: Apple claims that Samsung's tablets are copies of the iPad. While they do look similar, Samsung has claimed that there is no other logical way to design a tablet. Tablets are bound to look similar just the way that all cars have the same basic design, all TVs have the same design, and all pens have the same design. Why should this case be any different?

GC: "Apple apparently believes that a substantial amount of the success competitors are experiencing results from using innovations of Apple and designs associated with Apple. Apple is using these patent and trade dress claims to protect its investment in these assets, which it perceives to lawfully own for its own use.

"For example, while all cars have four wheels, a windshield, doors and fenders, not all cars need to or do look the same at a more detailed level. If Ford offered a car that looked essentially like a Corvette, one could easily imagine GM suing Ford for similar claims."

This is an angle that I hadn't considered. While there are only a few logical and functional designs for a car, that doesn't mean they all look exactly alike, nor should they. A Corvette and a Mustang both have four wheels, a frame, and a windshield. While these functioning parts are similar, the overall design and style are different for each car. However, Samsung made an interesting argument in the Preliminary Injunction case, saying that the core of Apple's design patents is "minimalistic." According to the Order Denying Motion for Preliminary Injunction, "Under this theory of design, ornamentation is stripped down to pure functionality, and therefore, Samsung argues, the D'677 and D'087 [iPhone-related] patents are invalid based on functionality." Mr. Carr commented on why this could be detrimental to Apple if Samsung is successful in proving its point in trial:

GC: "Design patent and trade dress protection is limited…If Apple asserted a design patent or trade dress that was so general it would have to be used by competing tablet manufacturers (e.g. rectangular, with a screen on one side and flat), the design patent and trade dress would be considered 'invalid'."

It would appear that Apple's patents and trade dress claims are too general. Even the hypothetical example that Mr. Carr gave of a design patent that would be too general ("rectangular, with a screen on one side and flat") is one of the very design patents that Apple is claiming as its property. Therefore, it is Samsung's goal to prove that these patents are invalid based on the argument that they are primarily functional. Apple would have to prove that other designs are possible. Apple gave a few alternative design options for smartphones. These designs contain: "more deeply rounded corners that gave an overall less rectangular visual impressions; sharper corners; differently shaped speakers; differently sized and placed screens; and alternative designs with additional buttons."

The Court felt that, though the patents themselves were not invalid based on functionality, certain aspects of the design were "dictated by functionality" and should not be considered part of the invention. When referring to other claims by Apple regarding its D'087 (iPhone) patent, the Court said that Apple had not persuaded the Court "that it is likely to succeed at trial in the face of Samsung's challenge to the validity of the D'087 patent." Interesting.

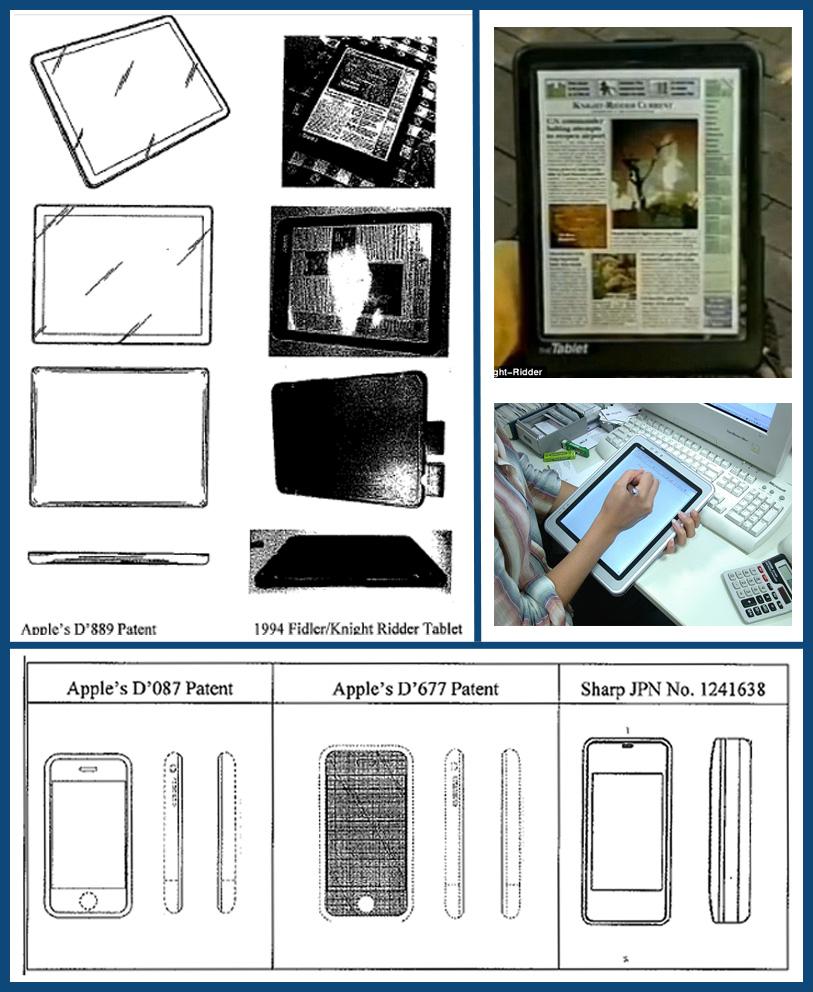

From Top Left clockwise: comparison of Apple's D'889 (iPad) patent to the 1994 Fidler/Knight Ridder tablet; Image of Fiddler/Knight Ridder tablet; image of HP Compaq PC TC 100 from 2002; comparison of Apple's D'087 and D'667 (iPhone) patents to Japanese No. 1241638 patent from 2005.

Prior art is a large part of Samsung's case. The company cites a Japanese patent filed in June 2005, more than a year before Apple filed one of its iPhone-related patents in January 2007; the Fidler/Knight Ridder tablet referenced in 1994; and an HP Compaq tablet from 2002. At least for this case, the Court found this prior art to prove Samsung's point of an "obvious" design choice for any tablet-maker.

Finally, what does this decision tell us about the outcome of the trial? How will it end? I asked Mr. Carr about that.

GC: "To some degree, the outcome at this point should shed light on the probable outcome. However, that would be more the case if the court granted the injunction, than by its denial. Denial could be the result of either a lack of fully developed evidence or the merits.

"It may surprise you that about 98% of all patent suits settle without trial. My sense though, is that Apple may want to take one or more of its claims to trial, if Samsung will not agree to stop using the alleged design or trade dress feature. If Steve Jobs was alive, that would probably happen. He was successful in proving that source code and object code could be protected by copyrights back in the 70s and 80s. But, less passionate minds at Apple may be content to charge Samsung and others a license fee to do so. If so, and of course if Samsung is willing to pay, then the case will settle."

So, our initial hypothesis was correct. This is personal for Apple and, while there's a chance that Apple will be willing to settle out of court and be content with a license fee, there's also a chance that Apple will continue Steve Job's "thermonuclear war" on Android and will not stop until the competing OS is gone.